Chinese composition mistakes can make kids want to pull their hair out.

To ensure nothing is done wrong to avoid being slapped with unexpected point deductions makes it even more challenging.

Unlike primary school compositions, secondary school composition writing usually breaks down into three types: narrative, descriptive and argumentative.

Here, we’ll be highlighting narrative compositions as it’s one of the prevalent choices among students. Descriptive compo writing, which usually entails greater vocabulary, and argumentative/expository essays that require knowledge of the craft, could be hard for students weaker in the language.

FREE TRIAL LESSON: LEARN HOW TO WRITE GREAT COMPOSITIONS ONLINE [30-SECONDS FORM SIGN-UP]

In this post, we’ve rounded up some of the most commonly made mistakes when students are writing and what are can be done to counter them. Check them out below.

Common Composition Mistakes That You May Have Missed

Here’s the thing: your kid works hard. And when they’re working hard without a plan in place for the grades they want to score, they fail repeatedly.

Just like with any other exams, a successful learning strategy requires regular practice. AND to identify and change the mistakes they may be making. We highlight the ten mistakes that most regularly turn up in Chinese composition writing. Start addressing these issues, and your child will immediately see a change in their grades.

1. Not strategically inserting dialogues

It’s perfectly fine to insert dialogues into writing, or even begin the composition with one.

But, we don’t recommend injecting dialogues in the middle of the essay, especially if the writer is not a master of words.

Dialogue is the fastest way to improve a manuscript—or to sink it.

The intention is not to restrict creativity. But without certain writing skills, the writing may digress from the topic. That makes it difficult for readers to catch on, which is a major pitfall.

2. Lacking imagination

When hundreds of students are writing on the same topic, guess what you get?

Predictability. Say, for example, the student is supposed to write a narrative essay about a surprise party. So here’s the standardized version of a Chinese composition: a friend is having his/her birthday soon, the group of friends plans a surprise birthday party, the surprise is revealed and everybody is happy.

It may seem like a foolproof essay-writing formula. As safe as they are, banality could still be penalized.

Readers like a crisis. They want to be nervous about what’s coming up next.

If a reader read something they’ve expected, there’s no more fun to it. The work is then nothing but a monotonous ride down the same route.

Other than the standard problem/conflict and resolution, it’d be good to put a spin in the story.

3. Not taking the 5Ws+1H seriously

As artistic as Chinese writing can be, there’s a certain structure to it. Almost all writers use the 5Ws+1H trick. English or Chinese, the 5Ws+1H is a good skill to a joint narrative for constant attention.

By sticking close to this trick, the story plot will have fewer breaks and put a naturally good flow to it.

For instance,

这时,一阵清脆悦耳的门铃声响了起来,原来是我的好朋友邓梦阳来了,我兴高采烈地和她向小区的那片空地跑去。

At first glance, it appears fine. However, with scrutinization, there’s a slight lack of a link between the sentences, with the apparent ‘why’ missing.

But add the ‘why’ in…

这时,一阵清脆悦耳的门铃声响了起来,我打开门一看,原来是我的好朋友邓梦阳来了,她约我与她一起去外面打雪仗。于是,我兴高采烈地和她向小区的那片空地跑去。

… and you get a clearer picture.

4. Too many clichés

Well, we’ve talked about using cliché phrases when penning a story several times. (Read 风和日丽) They’re not forbidden but it’s best to avoid them as much as possible.

One or two are fine, but too many make it hard for markers to connive. As much as many would like to believe, abusive use of clichés is in fact considered lazy.

Since writing is supposed to be a creative process, there’s really nothing creative in reusing trite phrases. Read 10 versatile and also interesting Chinese phrases and idioms for composition writing.

5. Too little emotions

Readers love a story that reminds them of a wild and wonderful rollercoaster ride. Going deeper into character building is the surest way to accomplish that. Your words are like the strings to an unanimated puppet. Every word you use brings life into the character.

Since fluff in the story is discouraged (go back to cliches), you’d need to work on the protagonist and give it a breathing, living personality.

Write about their flaws, the pain they’ve been through or the desires that shape them. With a strong character, readers are able to connect with the protagonist and the story better.

Before you start writing, plan out the types of language techniques you would like to use to convey emotions effectively.

These are some great techniques for that purpose:

五官描写 — Describing face features or facial expressions

行动描写 — Describing actions or movements. Some examples are like 啜泣、深吸一口气、皱眉头.

心理描写 — Write in details about the person’s thoughts such as internal conflicts or their worries.

比喻句 — Using items or objects to represent something tangible.

比拟句 — As opposed to 比喻句, this is used to personify or humanize items or objects.

Additionally, they put flesh on the bones of the overall content.

6. Weak language foundation

It’s painful not to be able to convey the message you have in mind. To do that, you need an extensive range of vocabulary.

Here’s an example,

很开心,不禁流下了眼泪。

This showcased the writer’s limited vocab.

In severe cases where students lack grammar and language skills, they may face difficulties in constructing sentences.

7. Way-too-direct narrative writing

她突然感到肚子有点饿,便去吃饭。

How do you feel about it?

A sentence such as this says nothing much except for being narrative. But by adding a tiny touch of motion, you’ll bring some subtle complexity to the story.

她突然感到肚子有点饿,便蹑手蹑脚往摆满饭菜的餐桌去,小手灵敏地把饭菜都送进嘴里。

Sometimes the pressure of trying to write creatively feels like too much. When your mind is in a blank, revisit some of the written sentences and add in some actions and motions.

8. Choosing the wrong topic

Most teachers are pretty confident in one particular area regarding writing: students with a weaker grasp of Chinese are recommended to attempt either narrative or expository composition.

Most students should be familiar with narrative writing as they‘ve been dealing with it since primary school.

As long as the writing stays on topic and techniques are being used properly, good scores shouldn’t be an issue.

As for expository writing, the topics learnt are similar to those of oral examinations, thus it’s not too hard for them to regurgitate the points.

Plus, as long as students follow the standardised template for expository composition, it shouldn’t be too hard for them.

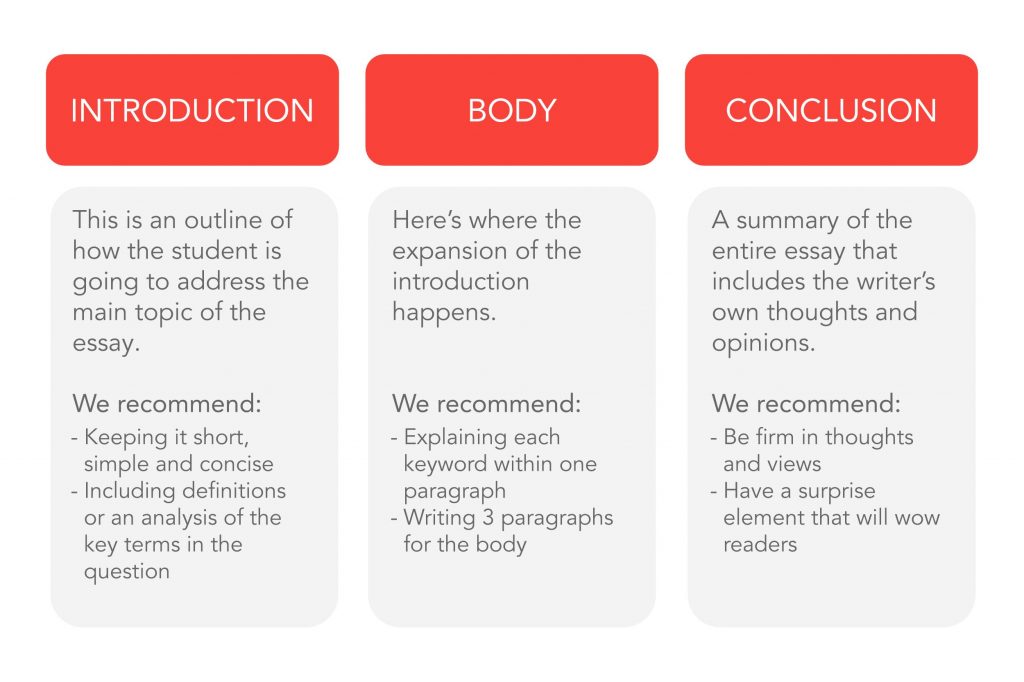

The usual expository/argumentative composition involves:

- Content – Logical thinking

- Flow – structure

- Essay organisation

- Flow of narrative

- Language

Here are some Chinese compo example questions:

- 最近,你的学校在全国校际比赛的决赛中遇上了夺冠的热门队伍。然而,你的学校出乎意料地击败了这个强劲的对手。描述你校努力赢得比赛的过程,并写出你从中得到的启示。 ( O level 2017 Q3)

- 只有目标而没有计划,是不可能成功的。试加以讨论。(O level 2017 Q4)

- 新加坡的社会充满爱心。你同意吗?为什么? (O level 2016 Q3)

They may seem like easy tasks since they feel like ‘common sense’.

But keyword, feel. There’s usually more to it than meets the eye.

To write a passable Chinese expository/argumentative compo, you need a good combination of the content, flow, and language.

Let’s say the topic is on resolving the problem of helping victims of school bullying. It’ll be best to give tangible and explicit suggestions of what the school can do to solve the problem.

For parents looking to grow their list of what-to-dos to help their kid reduce composition mistakes, we’re here to share them with you. You could be taking the first step to change the way your child learns Chinese.